South jersey piano

Supporting the musicians of southern NJ since 2010

Our Services

Piano Moving

We offer professional piano moving services for uprights and grands throughout southern NJ and surrounding regions.

Piano Tuning

The lifeblood of piano maintenance. Most pianos are tuned annually or biannually, more frequently for heavily played or performance venue pianos.

Piano Sales

We have a small selection of used grands and uprights for sale. If you are looking for something specific, we’d be happy to help!

Studio & Rentals

We can provide both short-term event rentals and long-term home rentals of uprights and grands. Our recording studio houses a pristine, immaculately maintained Yamaha C7 semi-concert grand which is also available for rental or studio sessions.

Other services we offer

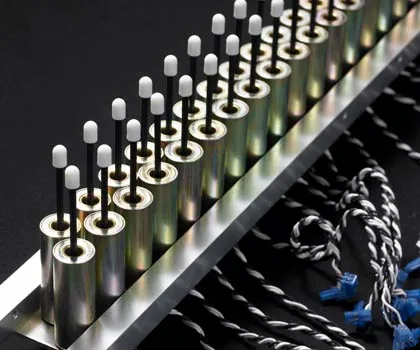

Piano regulation

We’ll adjust the mechanical action of the piano to give proper touch, response, and control Read more

Piano voicing

We’ll refine the tone quality, attack, sustain, and timbre of your piano Read more

Keytop replacement

Refresh your piano’s look with new key-tops Read more

Piano finish repair

We do on-site and shop repairs, and can refer to other specialists for more complex or unusual jobs Read more

Piano Lifesaver humidity control

We install a humidity control system designed to help your piano last longer and maintain greater tuning stability Read more

Piano appraisal

Get a thoroughly documented report on your piano’s condition and market value Read more

Read more

Highly recommended for those who care about keeping their pianos in tip top shape.

Put your piano in the hands of true musicians and piano experts

With South Jersey Piano, you can be assured that your instrument will sound better than ever and stand the test of time.